In 2019, I was hired by Heritage Toronto to write display copy about The ArQuives for a historical pillar and also write a longer history for their files. Then I kind of forgot about it. Yesterday I noticed it as I was walking to work and thought I’d snap a photo.

The ArQuives is the largest independent queer archive in the world and collects materials on a national level. It’s such an important repository of Canadian history, and I was honoured to be hired.

In this post, I share a bit more about what went into the research, as well as the results of that work.

A brief note on the pillar text itself: it’s actually incorrect. It looks like an error was introduced somewhere in the editing process, which I was not consulted on. When it was founded in 1973, it was actually established as the Canadian Gay Liberation Movement Archives, and renamed Canadian Gay Archives two years later. However, at the time the pillar text was being written, The ArQuives was newly renamed from the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives to The ArQuives, which may have been a source of confusion for the editor.

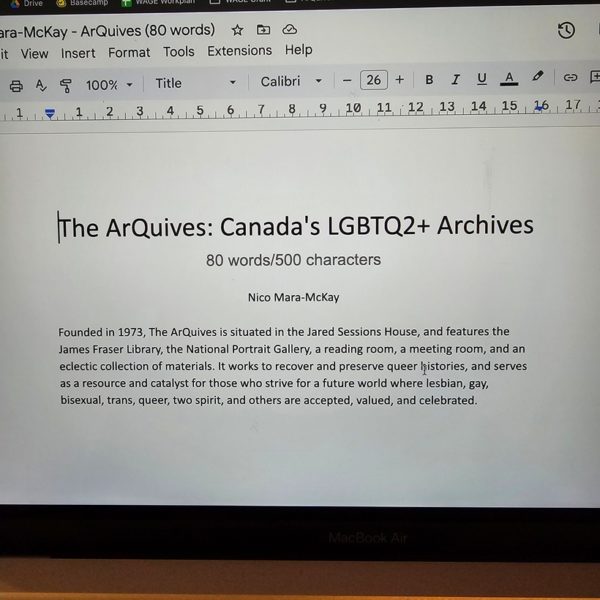

I only had a few words and characters to sum up the history of a (then nearly, now actually) 50 year old organization, which was quite a challenge. I’m glad that most of the text was kept, especially the explicit mention of trans and two spirit folks.

It’s funny to me that these few words simultaneously represent the most public thing I’ve ever published and also the most anonymous.

As a part of the work for Heritage Toronto, I also drafted a 1,000-word history of the organization, a version of which I will share below. I’m not sure what happened to that history. It’s probably in a government folder somewhere. The original was appropriately footnoted, but Patreon doesn’t allow for footnotes; instead, a bibliography follows. Anyone interested can contact me for specific references.

When I wrote this, I had just finished interning at The ArQuives as a part of a credit course during my last year of undergrad at the University of Toronto, and was looking for work before I would begin my master’s in the fall. A lot of the background knowledge and research came from my time working there on the Genderqueer in Canada digital exhibition. (More on that in a future post, maybe?) Additional sources were recommended by the executive director of the organization, as well as through searching through what was available through my institutional access at the University of Toronto. Of course, as always, there were nifty things I didn’t have the space to include in such a brief account, but that’s always the case.

Archives have a history of their own, and The ArQuives’ history has always been a political one. I hope you enjoy this brief introduction to what it is, what it does, and whose interests it aims to serve.

The ArQuives: Canada’s LGBTQ2+ Archives: A History

History

Situated in the heart of Toronto’s LGBTQ2+ Church and Wellesley Village, The ArQuives is located at 34 Isabella Street, just east of Yonge Street. Its current location, the Jared Sessions House, was purchased for one dollar by the organization from the Children’s Aid Society in the winter of 2006. The house was built between 1859-1860, and required renovations to suit the needs of the archive, in keeping with the requirements set by the Heritage Preservation Services, as this is a heritage property. In 2009, The ArQuives moved in.

The ArQuives emerged out of the student activism and the materials gathered by the collective behind Canada’s first queer magazine. Founded in 1971 by Jearld Moldenhauer, The Body Politic was the most widely circulated queer news magazine in Canada. By 1973 the magazine was run by a collective. Moldenhauer and Ron Dayman, another member, recognized the value of the material they had acquired, including that which was not being used for publication. That fall Dayman announced the creation of the Canadian Gay Liberation Movement Archives, which was intended to be national in scope. Donations were solicited through advertisements in the magazine, as well as by contacting lesbian and gay organizations across Canada. In 1975, it was renamed to the Canadian Gay Archives (CGA), and was under the care of Edward Jackson. After fighting for recognition as an archive and as a nonprofit. The CGA was incorporated in 1980, and established a board of directors, though the day-to-day affairs continued to be managed by the Archives Collective. In 1993, the board of directors elected to change the name to the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives (CLGA) in order to be more inclusive, and in 1995 the website was launched. In a further commitment towards inclusion, in March 2019, the CLGA became The ArQuives: Canada’s LGBTQ2+ Archives.

Steven Maynard cited the founding of this archive as the “beginning of a self-conscious gay history movement in Canada.” That this archive remained independent was and continues to be important, though that was not always guaranteed. In 1975, the Archives of Ontario offered to acquire some of the holdings from the Canadian Gay Archives, and that offer was rejected. Marcel Barriault called this “a politically empowering act,” as it kept the control of this material in the hands of the community that it represented and served. This included and continues to include materials that other archives might not preserve.

To read the full post, “A pillar of queer history in Toronto,” please subscribe to Ephemeral Record.

Pullquotes